The Big U in New York City by Rebuild by Design.

I continue my blog series on most flood-resilient cities around the world by exploring the nature-based solutions (NbS) adopted by New York City and London. While both cities face similar challenges from sea-level rise to extreme weather events, their strategies reveal contrasting priorities.

On the one hand, we have New York's emphasis on biomimetic, ecological solutions. This strategy plans to create infrastructure that improves over time thanks to regenerative practices, that build resilience through biodiversity and natural system restoration.

On the other, London's methodology which integrates flood resilience into every aspect of urban governance and development. In so doing, the city focuses on systematic risk management, regulatory frameworks, and coordinated infrastructure investment guided by long-term strategic planning.

New York City: living infrastructure

New York is pioneering a living infrastructure that adapts, integrates, and improves the quality of urban life while protecting against floods.

The Living Breakwaters during sunset by Baird for New York State.

The Living Breakwaters to contrast climate change

Rather than erecting static seawalls that require constant maintenance and gradually deteriorate, New York's 2015 Living Breakwaters project creates natural buffers that become more effective as oyster colonies grow and expand. These living systems absorb wave energy while filtering harbour water, removing pollutants and improving overall ecosystem health.

Nestled off Staten Island’s Conference House Park shore, in Tottenville neighbourhood, the Living Breakwaters redefine coastal defence through nature-based engineering. Winning the Rebuild by Design Hurricane Sandy competition, the initiative involves 731 metres of submerged breakwaters using stone and bioenhancing concrete to dissipate wave power and reduce coastal risk.

Hurricane Sandy claimed 44 deaths and inflicted $19 B in damages and lost economic activity across New York City in late October 2012. We owe the project to this tropical cyclone that impacted the Caribbean and the East Coast of the United States in late October 2012. The event caused significant coastal flooding, particularly in New York and New Jersey.

The solution builds a set of breakwaters, each inserted between 240 and 548 metres offshore. Ecologically, the breakwaters introduce geometries that mimic natural reefs, creating diverse intertidal habitats.

This design supports oysters, shellfish, juvenile fish, crabs, seals, and seabirds, re-establishing marine life in the Raritan Bay. Hosted by the Billion Oyster Project, oyster spat grown in local schools will be deployed on site through 2025.

Living Breakwaters in New York City as an oyster restoration project by Billion Oyster Project.

A Citizens Advisory Committee and collaboration with NYC Parks, Homes & Community Renewal (HCR), Billion Oyster Project (BOP), and local schools have granted active community stewardship. Women’s boat clubs, kayak classes, and environmental education are available at water hubs, that act as local entry points for public outreach, recreation, and science engagement.

The project saw its formal completion in late September 2024. It cost $111 M, out of which $97 M came from federal investment via HUD’s (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development department) Community Development Block Grant. Awarded the OBEL Prize in 2023 and the ACEC-NY Grand Honor Award in 2015, Living Breakwaters is a living testament to the idea that effective defence can and should be inherently restorative.

The BIG U: community-centred climate resilience

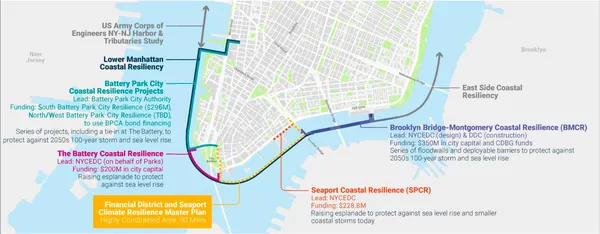

The BIG U proposal — equally born from the 2013 Rebuild by Design Hurricane Sandy competition — extends along the 16-kilometre coastline that goes from West 57th to East 42nd Street. The project encompasses several initiatives: East Side Coastal Resiliency (ESCR), Brooklyn Bridge Montgomery Coastal Resiliency (BMCR), Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency (LMCR), and Battery Park City Resiliency Projects.

Each segment combines sculptural berms, deployable flood walls, green corridors, and infrastructure camouflaged as public amenity. Rather than developing monolithic defences, the design divides the shoreline into 3 distinct compartments, each tailored to local geography and community needs: East River Park; Two Bridges/Chinatown; and Brooklyn Bridge–Battery. These sections act independently to contain flooding but unify into a cohesive shield, ensuring that a breach in one doesn't compromise the others.

Bjarke Ingels Group collaborated with community planners and landscape architects to hold workshops with over 150 residents, businesses, and non-profits. These installations are purposefully integrated into everyday life. Its participatory design delivers a protective infrastructure system that doesn’t feel like a fortress, but like home.

Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency programme

Echoing BIG U’s ethos, Battery Park City projects — South Battery Park City Resiliency Project (SBPCR), Battery Coastal Resilience Project, North/West Battery Park City Resiliency Project (NWBPCR) — are retrofitting waterfront spaces to integrate flood defence with nature and community life but are executed under the Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency programme.

Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency by FiDi and Seaport Climate Resilience Plan.

These projects interpret the BIG U vision in ways that respond to local context, funding streams, and community input. While they function under distinct administrative umbrellas, their shared DNA is unmistakable

Sustainable Drainage Systems (SUDS)

New York adopted citywide Sustainable Drainage Systems (SUDS) to transform the treatment of stormwater. SUDS regulate and distribute water management by capturing rainfall where it lands.

In particular, SUDS collect water via green roofs, rain gardens, permeable pavements, and swales. At each stage, water is slowed down, treated, and stored so excess flows are managed incrementally.

Devices like detention basins and retention ponds temporarily store water onsite and slowly release it, either returning it to the ground or conveying it in small quantities. This approach considerably reduces flood risk and sewer overload during heavy rain events.

SUDS promote ground infiltration through permeable paving, soakaways,¹ and infiltration trenches,² restoring aquifers and reducing runoff. By capturing water onsite, SUDS can reduce peak runoff and filter pollutants and sediments before they reach groundwater.

Kerbside rain gardens & porous pavement that are flash flood proof

Built in partnership with NYC DEP, DOT (Department of Transportation), and Parks, 5,000 kerbside rain gardens have been built in Brooklyn, the Bronx and Queens, on top of the existing 4,000. The Green Infrastructure Program(comprising more than 12,000 installations) is part of the City’s $23.5 B strategy to address climate change.

Kerbside rain gardens are planted depressions along sidewalks that capture runoff from streets and gutters. Each garden manages up to 2,500 gallons (approximately 95,000 litres) per storm, retaining water within 48 hours.

In combination with SUDS, rain gardens help reduce Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) in water-sensitive streets. These systems slow, filter, and detain runoff before it reaches overloaded sewers.

The Rain Garden Stewardship Program encourages community members to actively participate in maintaining local rain gardens. As of late 2022, the programme engaged over 50 local volunteers, managing upkeep such as weeding, debris removal, and soil upkeep to ensure gardens function effectively and look inviting.

Kerbside rain garden in Flushing, Queens, by NYC NYC Environmental Protection.

The City is also rolling out a porous pavement initiative along 11 km of Brooklyn roadways. Announced in September 2024 and slated for completion by fall 2025, this $32.6 million project will channel stormwater directly into the ground, which stress about 60% of the city’s drainage system.

London: policy integration and extensive planning

London's Thames Estuary 2100 Plan (TE2100) extends far beyond the iconic Thames Barrier to encompass upgraded embankments, coordinated early warning systems, and green infrastructure networks.

TE2100 began in 2002 and culminated in its first strategy in November 2012. Its adaptive, long-term vision includes 3 main aims:

- creating climate-resilient communities;

- enhancing the Thames’ cultural and ecological value;

- pursuing carbon neutrality and biodiversity recovery.

Set up by England's Environment Agency, Thames Estuary 2100 Plan was split into 3 phases:

- 2012-2035. Maintaining flood defences and planning for the future.

- 2035-2070. Essential upgrading of flood defences, while creating more accessible riversides.

- By 2070. The future adaptation of the Thames Barrier will take shape, along with further upgrades of the Estuary's flood defences.

Flood resilience zones under the Greater London Authority

London's innovation lies in its flood resilience zones. These zones are treated as policy areas that integrate flood risk into planning decisions. This means flood protection becomes a consideration in every building permit, infrastructure project, and land use decision. Development becomes part of the solution, while comprehensive planning ensures these individual interventions function as components of a larger, coordinated system.

These zones within the city require boroughs, the Greater London Authority (GLA), and the Port of London Authority to co-design Riverside Strategies by 2030, guiding developers to co-fund and co-deliver the construction of defensive infrastructure alongside new regulatory guidelines.

By 2030, these Flood Resilience Zones will be fully embedded into statutory Local Plans, requiring development proposals to complete SuDS strategies, provide flood evacuation routes ahead of flood events, and participate in borough-level visioning exercises. This plan integrates flood risk decision-making into placemaking, ensuring that climate resilience is central to urban growth.

Among the TE2100-designated zone, we find the Royal Docks (London Borough of Newham) in East London; Tower Hamlets identified as a “critical drainage zone”; Hammersmith & Fulham with their refurbished riverside walls such as those at Swan Draw Dock.

Upgraded Thames Barrier & early warning systems

The iconic Thames Barrier, operational since 1982, is now maintained and recalibrated to handle rising sea levels and increased storm frequency until year 2100. Beyond green infrastructure, TE2100 coordinates hard defence upgradesthrough the TEAM2100's (Thames Estuary Asset Management 2100) integrated delivery team.

Since 2015 (and until 2025), this initiative has refurbished assets across 350 km of tidal defences, including embankments, outfalls, pumping stations, and secondary barriers. This set of interventions is expected to protect 1.4 million people and £321 B worth of property and infrastructure in the tidal flood plain throughout London, Essex, and Kent.

Canvey Island southern shoreline revetment against rising sea levels

Up to date, Canvey Island, Essex, is undergoing the largest and most significant idal defence upgrade as per the TEAM2100 programme. The initiative entails renewing the southern shoreline revetment, a 3 km stretch (in-between Thorney Bay and north of Leigh Beck pumping station) where the early 1980s erosion protection is being replaced with a durable solution of Open Stone Asphalt (OSA). This distinctive material remains porous to absorb wave energy, ensuring continued resilience in the face of sea level rise, climate uncertainty and risk.

Financed by up to £75 million of government funding over 2.5 years, the revitalised revetment also brings added environmental and community value, going well beyond its core flood-control function. Improvements include improved public access via widened seaward walkways, new beach steps, information boards, flowering grass seed mixes, and habitat rock pools that support biodiversity.

Canvey Island southern shoreline revetment project by Poundfield Precast.

Green infrastructure community networks

TE2100 elevates green and blue infrastructure alongside engineered defences, aiming for social, ecological, and recreational value. By 2030, the Environment Agency plans to work with riverside councils and communities to equip them with the knowledge and tools to stay safe from the increasing tidal surges and fluvial floods.

Riverside communities will co-design adaptation visions that include habitat creation (salt marshes, wet woodlands), and cultural protection (like historic piers or buildings) in areas interested by flood defence upgrades. This partnership approach makes sure flood defences contribute to biodiversity, and carbon storage, as well as community wellbeing.

Comparative analysis: NYC vs London, flood resilient cities

New York's ecosystem-based solutions create smart infrastructure that can evolve with changing conditions. The living breakwaters and the BIG U project become visible symbols of climate action while providing tangible benefits to specific communities. However, this methodology can create uneven protection across the metropolitan area.

Conversely, London's thorough planning results in coordinated protection across the entire Thames Estuary region, with a special attention to Flood Resilience Zones. The systematic approach provides more equitable protection thanks to the systematic integration of flood resilience and mitigation measures into every aspect of urban governance and development regulations.

¹ Soakaways handle and control concentrated flows from specific sources (like a downpipe). They are typically constructed as excavated circular or square pits filled with permeable materials like gravel, rubble, or specialised plastic crates.

² Infiltration trenches have a distinctly elongated shape. Filled with stone, they run alongside roads, car parks, or building perimeters.