Tunnel-like reservoir by the Japan Government.

Here’s to my third and possibly last episode in my blog series on most flood-resilient cities around the world. I’ll be exploring the nature-based solutions implemented in the urban development of Tokyo. With a population of over 14 million residents as of 2023, Tokyo's urbanisation sits on a low-lying region, making it particularly vulnerable to floods and stormwater inundation.

As climate change brings more frequent, intense rainfall events, the stakes are rising for a megacity that has long been building resilience into its base. G-Cans initative is just the latest layer in a rich history of robust flood control solutions (NBS).

In this article, I'll explore how regulating reservoirs along with advanced underground tunnels, and real-time flood control, relate to today's Tokyo’s combined mature flood and storm management system for a changing climate.

Resilient Tokyo: staying strong against floods and earthquakes

Tokyo Resilience Project, launched in December 2022, represents perhaps the most complete urban climate adaptation initiative in the world. This ¥17 trillion (nearly €100 billion), 18-year strategy aims to fortify Tokyo in terms of changing climate and natural disaster risk management, from floods, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions, to power outages, and disease outbreaks. The project employs advanced digital twin technology and real-time systems integration to create a smart, responsive urban defence network.

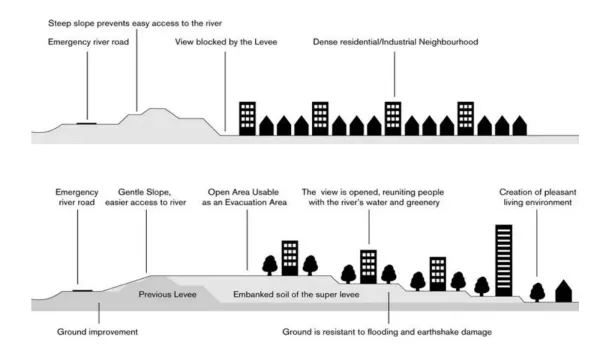

Yet, Tokyo has a long history of flood control, starting with the Arakawa diversion (1911–1930), built following the 1910 flooding. In 1987, the Arakawa-Karyu River Office resolved to upgrade the 30-meter-high river embankments by building super levees¹ measuring 300 m both in width and height. They did so predicting that a new flood could cost up to ¥35 trillion (almost €202 billion) in damages. Interestingly, the super levees allow the water to slowly flow across their top surface.

These structures absorb seismic stress and provide higher evacuation routes. Rather than creating barriers that separate communities from their rivers, these elevated parks bring people closer to the water while providing protection. Similarly, rivers can be systematically widened and fortified, to reduce the risk of riverbank collapse and increase capacity.

Traditional and super levee compared by Arakawa-Karyu River Office and MLIT.

With the increasingly frequent occurrence of localised cloudburst events such as the one registered in 1999, TokyoMetropolitan Govenment (TMG) came up with the creation of regulating reservoirs across the city. Let's then discuss this solution in detail.

Combined stormwater management as a flood control measure

Tokyo's approach demonstrates the city's comprehensive understanding of urban water systems. The city has implemented 28 reservoirs throughout 12 rivers with a combined capacity of approximately 2.56 million cubic metres. Among these 28 floodwater storages, we can identify:

- 16 in-ground reservoirs;

- 9 underground vaults;

- 3 underground tunnels.

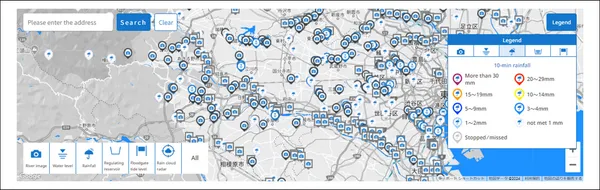

Tokyo's Flood Control Integrated Information System (FCIIS) collects real-time data on rainfall, river water level, tide level, etc., via rain gauges and water gauges. Thanks to sensors and observation data, Tokyo is able to perform flood forecasting and to monitor river and dam conditions.

Flood Control Integrated Information System (screen example) by Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

The infrastructure temporarily stores water to prevent overflow during extreme rainfall events. When Typhoon Hagibis (Typhoon No. 19) dropped record rainfall of up to 32 mm per hour (for a total of 240 mm) on the Tokyo region on October 12th, 2019, Tokyo’s reservoirs nearly reached capacity: one vault was 98% full, while another tunnel 91% full. Sihan Li and Friederike E. L. Otto (2022) estimate that about $4 billion of the insured losses ($10 billion) can be attributed to climate change. Their findings also show that this extreme event was made about 67% more likely due to human-caused climate change.

G-Cans: Tokyo's underground fortress to mitigate flood and storm risk

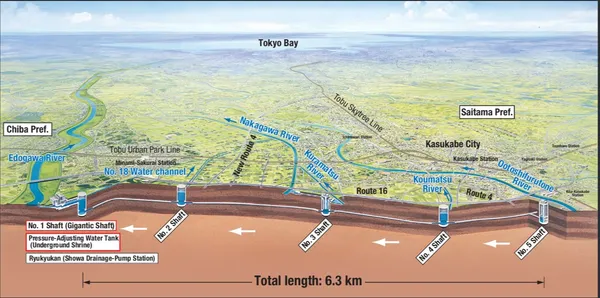

Completed in stages between 1993 and 2006, G‑Cans represents an ambitious underground flood management solution by the Metropolitan Outer Floodway Management Office. Officially known as the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel (MAOUDC), it has become famous for its pressure adjusting tank which is 18 metres high, 78 meters wide, and 177 meters long. It is located in the city of Kasukabe in Saitama Prefecture, 50 km north of Tokyo, next to the the Shōwa Drainage Pump Station, and is home to the Ryūkyūkan underground exploration museum.

Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel by the Metropolitan Outer Floodway Management Office.

G‑Cans comprises 5 intake shafts, each 50 m deep, and a network of 10-metre-wide tunnels culminating in the aforementioned cathedral‑like reservoir.

With powerful pumps, capable of expelling 200 tons of water per second into the Edogawa River, this subterranean facility actively reduces flood risk across vast urban areas.

Tokyo's G-Cans flood system overview map by ktr.mlit.go.jp.

G‑Cans has been triggered approximately 7 times per year, effectively preventing around ¥148.4 billion (more than €855 million) in flood damage by 2024, according to the the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT).

Beyond G-Cans, the Furukawa Reservoir (2008-2016) use 3.3 km of 7.5 m diameter tunnels to make up for the increased urban sprawl. This ¥24.5 billion (approximately €141 million) water regulation system handles the treatment of 135,000 cubic metres of water (equal to 54 Olympic-size swimming pools). The intake channel is positioned on the Furukawa Rivers's southern bank. Once rainfall eases, the reservoir discharges its water back into the river through pumps roughly 2 km downstream.

Furukawa Reservoir under construction in Tokyo, 17 August 2014, by Bloomberg.

Underground Kanda and Shirako reservoirs for a city safe from storm surge

By 1997, Tokyo had begun constructing Kanda River Underground Diversion Channel (Ring Road No.7). Recognising the increasing intensity of rainfall events exceeding 75 mm/hour, Tokyo launched a ¥37.3 billion, 7-year expansion projectin 2024.

This phase (to be completed by 2027) connects the existing Shirako River Underground Regulating Reservoir with the Kanda River and Underground Ring Road No.7 Regulating Reservoir (Shakujii River section) via a new 13.1 km tunnel-type reservoir, so that heavy flows can be redistributed among them. The combined reservoir will hold approximately 1.43 million m³ of floodwater. Discharge into Tokyo Bay is still under consideration.

Tokyo inspiring other Japanese cities to face the changing climate

Continuous adaptation, rather than occasional fixes, has allowed Tokyo to scale up defences. The combination of green spaces and river widening with engineered systems (tunnels, pumps, levees) shows that what works is integration across infrastructures.

The Tokyo Resilience Project, with its 100-year framing, emphasises both long-term vision and present urgency. It in fact acknowledges that climate change unfolds over generations. That balance between foresight and action is what gives Tokyo its flood resilience.

As the world warms and risks intensify, Tokyo weaves mitigation and adaptation into everyday life, using both nature and engineering to protect the city. Cities everywhere have something to learn from Tokyo's evolving infrastructure.

In this context, Tokyo Metropolitan Government runs G-NETS (Global City Network for Sustainability), namely knowledge-sharing visits with specialised staff in the sector. They invited professionals from 7 cities in Japan and abroadin late November 2024 to observe Tokyo’s underground regulating reservoirs. Also, in December 2024, representatives from 5 other cities toured the Minamisuna Stormwater Storage Tank in Tokyo to understand its design, benefits, and how public facilities can be built on top of such reservoirs.

Final considerations: turning resilience into civic life

The world's most flood-prone yet most flood-resilient cities demonstrate that effective climate adaptation transcends traditional engineering methods to drive urban transformation.

From Amsterdam's rooftop ecosystems that turn buildings into living sponges, and Copenhagen's courtyards that celebrate water as a community asset; to New York's take on nature to restore living reefs that grow stronger over time, and London's policy-embedded defences that guide development; or even Tokyo's underground networks that protect the wellbeing of millions of people — these cities prove that resilience can and should be regenerative.

The lesson from these leading cities is clear. The most effective flood resilience strategies don't just protect cities from water but help cities thrive with water, creating urban environments that are more liveable, sustainable, and resilient in the face of an uncertain climate future.

Decreased need for disaster response and infrastructure repairs

The economic case for flood-resilient infrastructure extends far beyond initial construction costs, delivering substantial reductions in emergency response expenditures and infrastructure repair needs. Comprehensive research demonstrates that proactive resilience investments generate significant cost savings through disaster reduction measures rather than responding to them after they occur.

In Tokyo, the greater quantity of damaged buildings prior to the implementation of the latest countermeasures speaks for itself. As per an intense rain event in 2005, an 80 mm/hour rainfall resulted in only 0.7 hectares flooded and 77 buildings damaged, as compared to 55 hectares and 621 buildings following Typhoon No. 18 (Typhoon Judy) in 1982.

3 men evacuate inundated areas, Typhoon Judy, Tokyo, 12 September 1982, by Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images.

Quantified cost-benefit analysis

The National Institute of Building Sciences (NIBS) has conducted a benefit-cost analysis of natural hazard mitigation. From adopting up-to-date building codes to addressing the retrofit of existing buildings and utility and transportation infrastructure, The Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves: 2019 Report found that mitigation grants save, on average, $6 for every $1 spent. This dramatic return on investment encompasses reduced emergency response needs, infrastructure repairs, and economic disruption.

The scale of potential savings becomes clear when viewed against current federal disaster response expenditures. FEMA's Disaster Relief Fund spent $47 billion in 2020 and $43 billion in 2021, the two highest annual totals in the program's history. These unprecedented spending levels reflect the increasing frequency and severity of flood events, making the case for disaster resilience investments even more compelling.

While, the World Bank's 2019 report Lifelines: The Resilient Infrastructure Opportunity provides global evidence for the economic benefits of resilient infrastructure investment. The study found that the net benefit of investing in more resilient infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries would be $4.2 trillion, with $4 in benefits for each $1 invested.

Reduced emergency service deployment

Flood proof cities experience measurably reduced demands on emergency services during extreme weather events. When infrastructure systems continue functioning during floods, emergency responders can focus resources on life safety rather than infrastructure failures.

This operational efficiency translates to cost savings through reduced overtime expenditures, equipment deployment, and coordination complexity. When critical infrastructure remains operational during floods, communities avoid the cascading costs associated with system failures while maintaining capacity.

Long-term infrastructure maintenance reduction

NIBS' research indicates that modern building codes incorporating flood resilience measures require minimal additional construction costs. Upfront investments in flood-resistant design and materials significantly reduce long-term maintenance and replacement costs in the long run.

Developing natural systems often become more effective as they mature, requiring less intervention and repair than mechanical systems that degrade with use. Look at New York's Living Breakwaters project whose very design supports the installation of oyster colonies off Staten Island’s shore.

Avoided economic disruption costs

Beyond direct infrastructure and emergency response savings, flood-resilient cities avoid the broader economic costs associated with business interruption, supply chain disruption, and community displacement.

Following March 2019 Cyclone Idai in the city of Beira, Mozambique, Dutch water experts estimated it would cost $888 million to rebuild with climate-resilient and neutral infrastructure and improve coastal protection.

Had resilience measures been implemented before the cyclone, such as improved drainage channels, protective dikes, and coastal ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA), the destruction could have been largely mitigated. Building resilience is not a luxury or a future-oriented ideal; it is an economically sound strategy that can safeguard both lives and public finances.

Universal principles from diverse approaches

Despite their different strategies, the world's most flood-resilient cities share several universal principles that transcend specific technical approaches or governance structures.

Integration over isolation

Successful flood resilience requires integration across urban planning rather than isolated water management infrastructure. Whether through Amsterdam's city-wide networks, Copenhagen's neighbourhood-scale integration, New York's ecological connectivity, London's policy coordination, or Tokyo's underground networks, effective resilience connects water management to transportation, housing, energy, and social systems.

Multiple benefits over single purpose

The most effective interventions provide multiple co-benefits rather than addressing flood risk alone. Amsterdam's blue-green roofs promote the recreation of natural habitats and mitigate the impacts of heat waves; Copenhagen's rain gardens create community amenities; New York's living breakwaters improve water quality; London's green infrastructure enhances air quality; Tokyo's super-levées create recreational space and contain earthquake damage.

Ojima Komatsugawa Park in Edogawa, Tokyo, by Expedia.

Adaptive over static

Resilient cities create infrastructure that can evolve with changing conditions rather than fixed solutions that may become obsolete. This includes New York's living systems that grow over time, Amsterdam's flexible water infiltration systems, Copenhagen's floating neighbourhoods, London's adaptive policy frameworks, and Tokyo's expandable underground networks.

Community-centred over technical

Successful resilience strategies engage communities as partners rather than passive beneficiaries. In fact, all these initiatives demonstrate that effective climate adaptation must enhance rather than constrain community life. With regard to London's Thames Estuary 2100 Plan, think of the inclusive initiatives that England's Environment Agency has lined up for riverside communities. Or again, the Living Breakwaters recognising the importance of building collaborations with local organisations and schools.

Systemic over piecemeal

Resilient cities understand that effective flood protection requires systematic approaches that address causes rather than merely managing symptoms. This includes London's Thames Estuary plan, and Tokyo Resilience Project for the next 100 years to come.

¹ A super levee is a specially engineered, reinforced river embankment. It is built to resist seepage, wave action, and earthquake effects, while often including urban public amenities. By design, it also tolerates overflow better than narrower, steeper conventional levees.